Infrastructure stimulus projects will almost certainly be part of our economic recovery. Continuing our conversation about Pandemic Strategy, this article focuses on the likely stimulus rollout schedule and, during the interlude, what strategic actions we should take to prepare.

Success happens so often to whomever is standing in the right place at the right time. Opportunity knocks and the lucky engineer, who’s just working away on regular projects, opens the door. Strategy, then, is when we make an effort to position ourselves behind the correct door in time for Opportunity to knock.

Sure, it takes work to decide the right place to stand and to know what staff, skills, relationships, and equipment you should have ready. It can be just as difficult to decide when, specifically, you’ll be expected to answer Opportunity’s knock. It’s important that you arrive neither so too early nor too late, to make the most of your preparatory interval, and to be fully committed to execution once it’s go-time.

While many of us complain about how large bureaucracies eschew innovation, predictability works to our favor when trying to predict the Federal responses to our developing economic challenges. They’ve got a playbook and for the most part they stick to it. We can predict the 2020 Pandemic stimulus response, more or less, by how they responded to past recessions.

Great Depression of 1929-1933

The Great Depression started with a stock market collapse in October 1929, and the economy didn’t stop contracting until March 1933. Key to the turnaround was a change from Herbert Hoover’s unsuccessful belt-tightening response to FDR’s energetic stimulus-based recovery. The incoming administration negotiated for wide-ranging reforms and stimulus spending over the first 100 days following inauguration, from January through March 1933. The New Deal, which included banking and securities regulations, a minimum wage, and a 40-hour work week, also included a $6 billion infrastructure investment. Valued as $120 billion in $2020, the New Deal public works projects finally put America’s withering construction industry back to work.

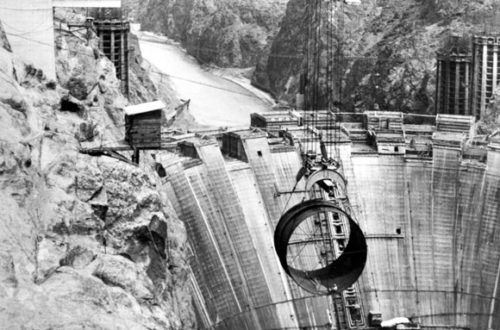

Notable New Deal projects include NYC’s Lincoln Tunnel, the Overseas Highway out to Key West, and the Hoover and Grand Coulee Dams. Companies that emerged from these contracts include Bechtel Corporation, Morrison-Knudsen (before a disastrous string of acquisitions), and Henry J. Kaiser before he got into shipbuilding and health insurance. The New Deal’s positive legacy begs the question: what if we had not squandered 4 years on austerity measures before pivoting to deficit-spending stimulus?

Great Recession of 2007-2009

The Great Recession of 2007 began in December when a subprime mortgage meltdown precipitated bank failures. The Bush administration took some time for Hoover-esque dithering in the run-up to the 2008 election, until in February 2009 the Obama administration (notably without Republican support) authorized stimulus spending through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

The ARRA included $165 billion of infrastructure spending, about a third larger than 1933’s program, but it rolled projects out much slower than had been hoped. Although generally regarded as a qualified success, the ARRA was simultaneously too large to attract Conservative support and too small to force a strong recovery. By 2013, four years into the spending, American economic recovery was best described as “slow and grudging.” Stimulus spending on infrastructure projects contributed to the recovery, but some economists suggest that a larger, and more rapidly-deployed, stimulus might have yielded better return on investment.

Pandemic Recession of 2020-2021(?)

The current recession is being managed more pro-actively than the 1929 or 2007 economic contractions. Still, though, it seems pertinent that both prior stimulus efforts were enacted shortly after a presidential election allowed the new Executive to claim a political mandate. In mid-June 2020, 4 months into the declared recession, our leadership is indulging their inner Herbert Hoover, dithering away their remaining time admiring the S&P 500 and hyping short-term retail sales improvement. They will not act before the November 2020 election.

The economy is unavoidably the key issue in November’s election, and whichever party is able to describe the best recovery plan will likely carry the House and the Executive. History suggests that they will claim their mandate within moments of the 20 January 2021 inauguration ceremony. By the following week, if history is any guide, the Congress should open debate on a tax-cut-plus-stimulus package. Despite everyone knowing that stimulus spending is the obvious response, the funds will not be authorized until mid-February 2021 and we’re not likely to be bidding infrastructure projects before next March.

Preparatory Activities

So what can we do over the intervening 9 months so that we position ourselves in the right place at the right time? For Atlas Geotechnical, the “right place” is the bid-preparation War Rooms of our strongest infrastructure clients. The right time is March and April 2021. We have 9 months to accumulate the financial resources to carry us through a period of intense bidding, plan our activities, adjust our staffing levels, and secure invitations to the winning teams. The right place and right time for your practice is surely different, but there’s no doubt that you should be planning your strategy so that you’re standing behind the right door when Opportunity knocks.

Start Recruiting: To the extent that you can, donate to, support, and visit the academic programs that train up your best new hires. Support your local gunfighters. You’re going to need new employees from the cohort that graduates in May 2021. You need to meet the young professionals who decide to wait out the lull by earning a Master’s degree. They’re going to be assembled and ready to meet prospective when they arrive on campus in 3 months. Make a plan to meet them, encourage them, financially support them, and then hire the best of them.

Refine Your Systems: Limber up and run some drills to prove that you’re ready to work. To design and build like you want, you should identifiy the current rough spots in your practice and polish them out. Frequent readers will recognize this as yet another recitation of “never waste a lull,” but that’s because it’s important and bears repeating. Never waste a lull. Get your financial systems in order, build up your warchest to the extent that you can – or line up some credit – update your safety manual, refine your report templates. Prepare yourself and your team so that when it’s time to do real work your underlying systems are ready to support you.

Exude Confidence: Know that the stimulus is coming. Be confident in yourself and make sure your crew sees you projecting that confidence like a Boss. You had a workable business plan before the pandemic tanked your backlog; your fundamentals are strong. Believe in yourself and your crew, and share how much you’re looking forward to working through the recovery with them. And for mercy’s sake hang on tightly to your key employees.

Rest: This recovery is going to be a marathon, not a sprint. We’re planning that it’ll take 3 years to spend our part of the upcoming stimulus. I’m preparing to work long weeks from Summer 2021 through the end of 2024. My son will be in graduate school. Your children will be older; your spouse may have retired. While we wait for the intense effort to start, we all should try to get some memories into the bank. Once we can travel safely, commit to that trip with your family. Take photos and set up a slideshow screensaver that buoys you up on future snowy airport layovers.

History is a great teacher, but you’ve got to go to class. All of the news that I’m reading suggests that the economy will contract over the next year, and all signs indicate that infrastructure stimulus spending will be part of the economic recovery by this time next year. By making most of the 9 months that our leadership requires to authorize this spending we all can be better prepared for success when Opportunity, predictably, knocks on our doors.